Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Thursday, April 5, 2007

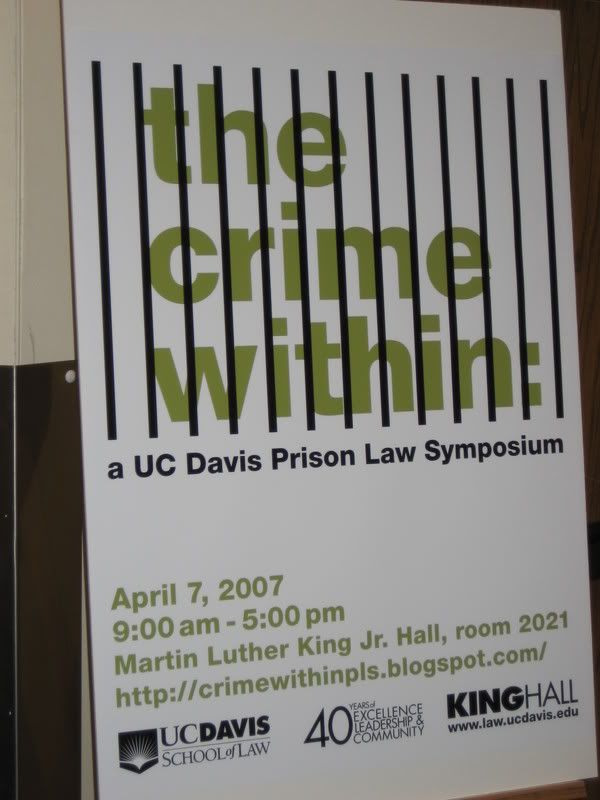

Annual Prison Law Symposium to be held Saturday

http://media.www.californiaaggie.com/media/storage/paper981/news/2007/04/05/CampusNews/Annual.Prison.Law.Symposium.To.Be.Held.Saturday-2825294.shtml

By: Allie Shilin

In response to Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's California Prison Overcrowding State of Emergency Proclamation on Oct. 4, 2006, the UC Davis School of Law will be addressing present conditions in California's prison system during their third annual Prison Law Symposium on Saturday."The state of emergency is basically just saying that the issues and problems can't be neglected anymore," said Phoebe Hyun, co-organizer and third-year UC Davis law student. "It has to be confronted and it has to be dealt with now. I think the state of emergency is just a solidification of how people are feeling. The governor and the state couldn't ignore it anymore."

The four-panel discussion will be held from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the Martin Luther King Jr. Hall in room 2021. Sixteen speakers from diverse backgrounds and expertise, including an 18-year political prisoner and members of the public defender's office, will discuss a variety of issues, including the present prison conditions, alternatives to incarceration and post-release issues, sex and gender oppression and the death penalty.

Kimberly Huangfu, co-organizer and third-year law student, said the symposium is relevant because the government "is spending so much money on the prison system, but [the public] isn't seeing any results."

Taking money away from social welfare programs and education is not the best way to alleviate the prison problems, and money instead should be shifted to prisoner rehabilitation, she said.

Students should attend the event, according to Hyun, because every person is connected to the prison system in one way or another, even those who have not experienced it personally.

"We get huge fee hikes every year ... and we're not just paying for our education," she said. "We're in a public school system. In this case, these prisons and the costs of these prisons are a big chunk of our budget right now.... Not only the tax dollars, but it's something that you're going to have to deal with. It has a trickle-down effect. How we take care of our law in society will come back around in some way or another."

Hyun and Huangfu expressed a deep concern for the people behind bars and their possible future if they assimilate back into society.

"When you label somebody as a prisoner, it kind of dehumanizes them and we're saying that it might have been a mistake," Hyun said. "It's not just about giving them a second chance. It's about doing the right thing and making sure that the prison system actually works. That prison system only works when they're rehabilitated.

"I don't think the problem is solved when you're throwing them back and forth into prison," she said. "It's far beyond that prison time. I think it's a part of considering these people as fully human."

Tuesday, April 3, 2007

Contact: prisonsymposium@gmail.com

"THE CRIME WITHIN: A KING HALL PRISON LAW SYMPOSIUM"

AT UC DAVIS School of Law

Davis, CA -- "California's correctional system is at a crisis point.” - Arnold Schwarzenegger. On Saturday, April 7, 2007, the UC Davis School of Law at Martin Luther King Jr. Hall will present "The Crime Within: A King Hall Prison Law Symposium." King Hall 3L and second-time prison law symposium co-organizer Kimberly Huangfu explains, "Considering the current state of crisis that the California Prison system is facing, conservatives and liberals alike are in agreement that something needs to be changed. Thus, we chose this year’s theme to reflect how our criminal justice system is failing to adequately serve the basic needs and rights of our nation’s prisoners."

Taking place in Martin Luther King Jr. Hall Room 2021 from 9:00 am until 5:00 pm, this third annual prison law symposium is free and open to the public. Speakers from a diversity of backgrounds and expertise have been invited to speak on four panels: Present Prison Conditions, Alternatives to Incarceration and Post-Release Issues, Sex and Gender Oppression, and Death Penalty. The first panel will include Holly Cooper, a King Hall graduate and supervising attorney for the Immigration Law Clinic on campus. This panel will also include, Ed Mead, a former political prisoner who served 18 years in prison for his participation in the George Jackson Brigade, a 1970s radical organization that engaged in armed actions against the state. Today, Ed mead is the President of the California Prison Focus and staff member of the Prison Art Project. Other panelists will include Monica Knox, a long-time public defender with the Federal Public Defender’s office whom has extensive experience with the prison system from both a professional and personal perspective, Gail Patrice from the Statewide Family Council, a group of family members and friends of prisoners that meets regularly with the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to create and maintain communication and a better understanding regarding the prisons, those they incarcerate and their families, and Debbie Reyes from the California Moratorium Project, an organization that seeks to stop all public and private prison construction in California. The second panel will feature Beth Waitkus, the Director of the Insight Garden Program at San Quentin which has involved a team of local landscapers, gardeners and community members, as well as prison inmates and staff to build and maintain an organic, native California garden on San Quentin's medium-security prison yard. Other speakers will include Lisa Rea and Russ Turner from The Justice & Reconciliation Project and Candlelight Foundation, respectively, who will speak on restorative justice and legislative reform. Lisa Rea is the president and founder of The Justice & Reconciliation Project (JRP) and has an extensive background in restorative justice with a passion for restoring victims of crime and communities while holding offenders accountable. Russ Turner, an award-winning director and producer of film, has spent 30 years working in the Criminal Justice System directly with the California Highway Patrol and The California Attorney General’s Office. He is currently working as a Crime Prevention Specialist with the California Attorney General’s Office in the Crime and Violence Prevention Center. Aside from discussing reforms and alternatives, Matthew Powers, Executive Director of PRIDE Industries’ new Re-Entry Services Division, will address the ever-increasing need to provide post-release services to former-prisoners. The third panel features Andrea Bible from Free Battered Women, which seeks to end the re-victimization of incarcerated survivors of domestic violence as part of the movement for racial justice and the struggle to resist all forms of intimate partner violence against women and transgender people. Other featured speakers include, Karen Shain, Co-Director of Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, Chris Daley, a staff attorney at Transgender Law Center, Maria Ortega, a member of the Trans/Gender Variant in Prison Committee -- a community organizing project of the Transgender, Gender Variant & Intersex Justice Project, and Lynsay Skiba from Justice Now. And lastly, the fourth panel, focused on facilitating open discourse regarding death penalty issues, will include Ellen Eggers, a Deputy State Public Defender in Sacramento for the past 17 years and Founder of the Sacramento California Death Penalty Focus Chapter, and Edward Bronson, Professor of Political Science and Public Law from Chico State, who has been involved in hundreds of death penalty cases for over almost 40 years.

The idea for the first prison law symposium in April of 2005 ("The Truth Unlocked: A California Prison Law Symposium") originated in a Judicial Process seminar taught by King Hall Professor Bill Hing. Always seeking to supplement coursework regarding the judicial system with other issues of legal significance, two years ago Hing sought the assistance of Susan Jordan, a 2L at the time, to present to the class regarding her expertise in the criminal justice system. A group of students in that class became inspired to create a symposium exploring the very timely and provocative issues and gathered support and funding to realize their vision for three years in a row.

With generous funding provided by the King Hall Annual Fund and American Constitution Society, breakfast and lunch will be provided on Saturday. The schedule for the symposium and more information about this effort can be found at the symposium blog: http://crimewithinpls.blogspot.com/. Any questions can be directly e-mailed to kimberly.huangfu@gmail.com.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Updated April 5, 2007

Saturday, April 07, 2007

9:00AM - 5:00PM (Breakfast and lunch served)

UC Davis School of Law – Martin Luther King Jr. Hall, Rm 2021

9:00 am - Breakfast, registration

9:30 am - The Crime Within: Welcome Address

Professor Jennifer Chacón, UC Davis School of Law

10:00 am - Present Prison Conditions

- Debbie Reyes, CA Prison Moratorium Project

- Ed Mead, President of the California Prison Focus and staff member of the Prison Art Project

- Monica Knox, Federal Public Defender

- Holly Cooper, Immigration Law Clinic

- Gail Patrice, Inmate Family Council of CSP Solano

12:30pm - Reform, Alternatives, and Post-Release Issues

- Russ Turner, Candlelight Foundation, Restorative Justice

- Lisa Rea, The Justice and Reconciliation Project

- Beth Waitkus, Director of the Insight Garden Program at San Quentin

- Marci Coglianese, Co-Chair of the Statewide Family Council

- Matt Powers, PRIDE Industries

- Karen Shain, Legal Services for Prisoners with Children

- Andrea Bible, Free Battered Women

- Chris Daley, Transgender Law Center

- Maria Ortega, Transgender Gender Variant and Intersex (TGI) Justice Project

- Lynsay Skiba, Justice Now

- Ellen Eggers, Attorney at the Office of the State Public Defender and Co-Founder of the CA Death Penalty Focus

- Edward Bronson, Chico State, Professor Political Science and Public Law

Office of the Dean, King Hall Annual Fund

Advocates for the Rights of Children

Agricultural Law Society

American Constitution Society

Black Law Students Association

Feminist Forum

La Raza Law Students Association

National Lawyers Guild

*This event is FREE and open to the public

Location: UC Davis School of Law -

Martin Luther King Jr. Hall

MCLE Credits

This activity is approved for Minimum Continuing Legal Education Credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of one hour, which applies to the elimination of bias credit. The

Registration for the MCLE credit will begin 30 minutes before the start of the lecture.

Directions to King Hall (Law School), UC Davis

80 East

Take Exit 71 (UC Davis) towards the Robert & Margrit Mondavi Center

Turn left at the stop sign (Old Davis Road).

Pass the parking structure.

Turn left at the stoplight.

Go past the stop sign, left at the roundabout, and park in front of King Hall.

80 West

Take Exit 71 (UC Davis) towards the Robert & Margrit Mondavi Center

Turn right at the stop sign (Old Davis Road).

Pass the parking structure.

Turn left at the stoplight.

Go past the stop sign, left at the roundabout, and park in front of King Hall.

Questions? Email prisonsymposium@gmail.com

Early release of inmates a possible solution to overcrowding

Governor, lawmakers seek solutions to ballooning prisoner population

Timothy Jue, California Aggie

February 26, 2007

With a state superior court judge's ruling that blocks the transfer of California inmates to privately run, out-of-state correctional facilities still lingering from earlier in the week, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger said he would consider the early release of prisoners to ease continual overcrowding in the state's prison system.Faced with pressure from federal judges to solve the prison overcrowding problem, and at the risk of a cap on the state's inmate population this summer, Schwarzenegger told reporters at a Feb. 22 capitol news conference that he would look into the possibility that sick and nonviolent prisoners could be released before serving their full sentences.

"We have to look at a [wide] variety of different things in order to solve this problem," the governor said. "But I think the important thing is that we've got to start working on it now, and we've got to take this seriously."

In January, Schwarzenegger proposed spending $11 billion to construct more state prisons and expand existing prisons to house more inmates. However, the construction of new facilities could take years to complete.

At the news conference, the governor talked about moving additional prisoners to out-of-state prisons as another short-term solution to the overcrowding problem, despite Sacramento County Superior Court Judge Gail Ohanesian's Feb. 20 decision to block the inmate transfer plan.

In her ruling, she said the governor inappropriately used his powers to declare that the crowded state prison system was under a state of emergency. The Emergency Services Act, Ohanesian wrote in her ruling, is intended to provide state assistance to burdened local jurisdictions in the event of natural disasters and other events.

"The intent of the Emergency Services Act is not to give the governor extraordinary powers to act without legislative approval in matters such as this that are ordinarily and entirely within the control of state government," the judge wrote in her five-page order.

The Schwarzenegger administration said it would appeal the ruling and made no plans to discontinue the inmate-transfer plan, which exports prisoners to institutions in Tennessee and Arizona.

"It ought to be more concerning to the public and the press what else can he declare a state of emergency on," said Chuck Alexander, vice president of the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, which sued the governor over the transfer plan along with another prison guard union.

Alexander praised the judge's decision but expressed frustration over the governor's approach in finding a solution to the overcrowding issue.

"It seems to be indicative of the style that the governor is using," he said. "He doesn't like to be told he's wrong by anybody."

Officials with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation estimated that, by this summer, the state's 33 facilities will run out of bed space for inmates. Currently, 172,000 inmates are housed in a prison system designed for 100,000.

Reposted from The California Aggie: http://www.californiaaggie.com/home/index.cfm?event=displayArticle&uStory_id=53a76e84-59cf-4865-96de-55a2a1165f0b

Grim conditions at youth prison

Report calls Chino facility lax, dangerous 2 years after governor vowed to fix system

Mark Martin, Chronicle Sacramento Bureau

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

(02-28) 04:00 PST Sacramento -- The state's largest juvenile prison provides virtually no education services to its wards, allows them to keep makeshift ropes in their cells and keeps most of them locked up 22 hours a day, according to a report Tuesday by the state inspector general.

The report, issued more than two years after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger promised to improve conditions inside youth prisons, concludes that the environment is so bad at the Herman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility in Chino that wards could be especially prone to violence or suicide.

Among the findings are that wards at Chino are allowed to cover their cell windows -- blocking prison staff from seeing inside. The practice, the report says, is particularly troublesome in light of a 2005 suicide at a Stockton facility in which a ward covered his cell window and hanged himself with a bedsheet.

The state inspector general's office, which acts as a watchdog over California's prison system, found that many of the conditions at the Chino prison mirrored those of the Stockton prison.

"You have the same kind of recipe brewing,'' said Brett Morgan, a spokesman for Inspector General Matthew Cate.

The review brought on harsh criticism from advocates for juvenile offenders who noted that the state has missed court-ordered deadlines to implement reform plans it agreed to when Schwarzenegger settled a lawsuit in 2004 over unconstitutional conditions inside youth lockups.

State Sen. Gloria Romero, D-Los Angeles, who has proposed shutting down the state's Division of Juvenile Justice, formerly called the California Youth Authority, said she "wanted to scream when I read this report.''

"Nothing has changed,'' Romero said. "We're dealing with an organization that is impervious to change.''

Cate's investigators visited Stark three times in 2006 and found numerous problems:

-- Inspections of cells designed for hard-to-manage wards found that more than half had prohibited items, from fabrics used to cover cell windows to makeshift ropes. One ward had constructed a large punching bag in his cell, another had 17 Styrofoam cups filled with ingredients for pruno, or homemade alcohol. Conditions at the facility "present an environment conducive to suicide attempts and potentially dangerous to staff,'' Cate wrote.

-- A review of 323 wards' records found that only seven were allowed out of their cells for more than three hours a day, and less than 1 percent of them received any educational services. There was one teacher for 54 wards in the living unit the investigators reviewed.

-- Wards received no discipline or only light discipline for sexual misconduct and appeared to receive relatively little treatment for sexual behavior problems before being released. The report notes that one ward convicted for lewd and lascivious acts exposed himself to staff members eight times and was kicked out of his treatment program but then was released from the system without any parole conditions.

The report reiterates many of the problems cited in 2004 throughout the youth prison system, when Schwarzenegger held a news conference at N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton to announce the settlement of a class-action lawsuit. The suit had accused the system of warehousing juveniles in prison-like facilities instead of providing education, counseling and mental health care.

The governor said then that the juvenile justice system should work with young criminals to help them change bad habits that could land them in prison, and his administration submitted plans in 2005 and last year to make changes in all aspects of the system.

But the department has missed several deadlines outlined in those plans, according to Don Specter of the Prison Law Office, which filed the lawsuit. Specter noted that the job of director of programs for the system is vacant.

"The person who's supposed to lead the transition hasn't been hired,'' he said.

A spokesman for the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which includes the juvenile justice system, said the department was beginning reforms, such as reducing the number of wards in living units and creating better sexual behavior treatment programs, that would affect Stark and other facilities.

"The (inspector general's) review came as we were submitting these plans, and we are now beginning significant reforms,'' said Bill Sessa.

Schwarzenegger administration officials have pointed to Chaderjian in Stockton as an example of positive change. The facility garnered notoriety during the past few years for a videotape showing guards beating two wards and for the 2005 suicide of ward Joseph Maldonado, who had been kept in near-isolation for eight weeks before his death.

The department reduced the number of wards at Chaderjian, which has housed most of the most dangerous youth offenders in the system. In 2006, the level of violence there went down.

But many of those wards were moved to Stark, and assaults there and in other youth facilities went up last year.

"They basically just shifted the problems,'' said Sue Burrell, an attorney for the Youth Law Center in San Francisco, who said she has received numerous letters and phone calls from wards and their parents saying wards at Stark have asked to be kept in their cells at all hours because they fear for their safety.

Schwarzenegger this year has proposed reducing the size of the youth prison system by giving counties block grants to house juvenile offenders locally. The idea is supported by many advocates.

"Shrinking the system is good in the long term, but right now we seem to be sacrificing the lives of many young people,'' Burrell said.

E-mail Mark Martin at markmartin@sfchronicle.com.

Repost from SF Gate at http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/02/28/MNGG7OCLJB1.DTL

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Don't Outsource California Prisoners

| Written by: Steve Fama, Prison Law Office |

| Article Last Updated:02/10/2007 07:15:46 AM PST Repost from Inside Bay Area, Daily Review, http://www.insidebayarea.com/dailyreview/oped/ci_5200960 |

| CALIFORNIA Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's plan to forcibly transfer California prisoners to private prisons in other states is a bad move. Private prisons are troubling to begin with. More than 150 years ago, California took over San Quentin from a private operator because of a series of scandals over prisoner mistreatment and incompetent guards. Private prisons today too often correlate with low employment standards, poor staff training and inadequate inmate protections. Self-interested private profiteers are not answerable to the public and shouldn't be given the job of locking people up. What's next, contracting out the Highway Patrol and police? Forced transfers are equally troubling. First, they're against the law. California requires that prisoners consent to out-of-state transfers. The courts sentenced convicted defendants to California prisons, not to Tennessee or Mississippi, far from the community to which they'll be paroled. The law requires a prisoner's consent because people incarcerated out of state enter a legal twilight zone. They continue to be governed by California laws and rules, but they are thousands of miles from the California courts that can enforce those laws and from lawyers who can best advise them. State officials say they can ignore the consent law because the governor has declared a state of emergency in the prisons. This is a dangerous precedent. The governor should not be allowed to choose which laws to follow. Besides, the laws about declaring emergencies are designed for the unexpected — an earthquake, for example — not a predictable crisis that has been growing for more than a decade and has been caused by mismanagement and governmental failure. It's pathetic that the same elected officials who for years have failed to address prison overcrowding now want to outsource their failure. They know what steps are necessary to solve the overcrowding problem, but they lack the political will to act. The problem is that we incarcerate too many people, especially nonviolent offenders. New York has reduced its prison population by more than 10 percent since 1999 by moving nonviolent offenders out of the system. California's refusal to take on that task means that even the cells freed up by forcing prisoners out of state will be quickly filled again. There is a sensible way to reduce the prison population relatively quickly. The prisons are flooded with parole violators — more than 60,000 a year — whose violations are minor. According to the state watchdog Little Hoover Commission, California's parole system greatly increases the chances that many will violate parole. Parolees are offered little or no help, and any mistake can result in a return to prison, even if it doesn't involve criminal conduct. They don't stay in prison long, but each one takes up resources that could be better used. One solution is a screening process, used in many other states, to determine which violators pose the greatest risk and need to be re-incarcerated. Because the executive branch controls the parole system, the governor could immediately implement such a program. If it resulted in only a 10 percent reduction in the number returned to prison annually, it would empty more beds in one year than the forced transfer of inmates. In the long term, California legislators need to fix the state's jumble of criminal sentencing laws. Enacted over the last 30 years, these laws require too many nonviolent offenders to be imprisoned for too long. California could establish a sentencing commission to address this problem. In other states, including Virginia and North Carolina, sentencing commissions have led to smarter incarceration practices, a reduction in crime and billions of dollars in taxpayer savings. Schwarzenegger supports the concept of a sentencing commission, but it isn't clear whether he wants a commission with real authority, which would be essential. A commission that could only make recommendations would be useless. Afraid of being labeled soft on crime, California's politicians in the Legislature and the governor's office have repeatedly failed to take real steps to reduce prison overcrowding, even though they know what must be done and why. The proposal to force prisoners to transfer out of state is just another way to avoid doing the right thing.

Steve Fama, a staff attorney for the Prison Law Office in San Rafael, represents inmates in cases involving prison conditions. |

Guantanamo court moves rejected

The provision was a key element of a law for prosecuting terror suspects that President George W Bush sent through Congress last year.

The appeal court said civilian courts could not determine whether detainees were being held illegally.

The ruling is almost certain to go to the Supreme Court, correspondents say.

Last year that court threw out the government's original plans for trying detainees before military commissions.

'Enemy combatants'

The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled 2-1 in favour of the provision in the Military Commissions Act.

Mr Bush had said he needed the new law to bring terror suspects to justice. It allows for the indefinite detention of foreigners as "enemy combatants".

Writing in favour of the majority decision, Judge A Raymond Randolph said that accepting the arguments of lawyers on behalf of detainees "would be to defy the will of Congress".

Dissenting Judge Judith W Rogers said district courts would be "well able to adjust these proceedings in light of the government's significant interests in guarding national security".

There are nearly 400 detainees being held at the Cuba detention centre.

Up to 80 are set to face the new military commissions.Tuesday, February 13, 2007

Under the Guise of Choice, Denying Justice to Women in California Prisons

Repost from http://www.rhrealitycheck.org/blog/2007/01/26/under-the-guise-of-choice-denying-justice-to-women-in-california-prisons

Two million Americans are currently living inside prisons, and although less than 10 percent of them are women, that statistic belies the fact that women are the fastest growing prison population in the United States—since 1980, the number of incarcerated women has risen by almost 500 percent. The steady increase in women's imprisonment rates is just one aspect of our culture's obsession with incarceration (we currently hold the dubious title of world leader in locking up its own citizens), fueled by an aggressive for-profit prison industry and a disturbing reluctance to engage in an honest national conversation about poverty, mental illness, drugs, and systemic discrimination, among other things.

In California, where 170,000 people are currently behind bars, the female incarcerated population has increased 43.6 percent over the last 15 years. Approximately 70 percent of these women are serving sentences for nonviolent drug- or property-related offenses, thanks to restrictive sentencing laws and aggressive three-strikes policies. Many of them are already mothers, and many of them enter the prison system pregnant or will become pregnant while serving out their sentences. Medical neglect of prisoners—especially when it comes to reproductive health—is commonplace (it's been estimated that someone dies each day in California prisons due to gross medical neglect). Women are often denied screening and treatment for cervical and other reproductive cancers and for sexually transmitted diseases, and pregnant women often receive grossly inadequate pre- and post-natal care, which has been known to result in preventable miscarriages. California outlawed the shackling of female inmates during labor in 2005, but human rights organizations like the Oakland-based Justice NOW that work directly with women in prison report that the practice has continued. Once women give birth, their infants are usually placed in state custody.

You don't have to be a prison abolitionist to recognize that this situation isn't helping anybody—not women, not their children, not their communities, and not the communities that are allegedly being "kept safe" by these women's incarceration. Which is why it's so disappointing that, under the guise of fixing the problem, legislation recently proposed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation's so-called "Gender-Responsive Strategies Commission" would actually make the situation worse. After identifying 4,500 women who should not be in state prison, the Commission proposed that they be relocated (or, in an interesting choice of words, "released") into "community-based treatment centers." Sounds great, until you realize that these "mini-prisons" are actually a thinly veiled attempt to hand new prison construction contracts to private contractors, thereby freeing up 4,500 beds for new inmates—which means that the whole plan is just a convoluted way to expand California's prison system. Maybe that's why one of the bill's original co-authors withdrew her support for the package, calling it "a fraud." Unfortunately, the proposal was reintroduced this year, despite opposition from its former co-sponsor.

Even more disturbingly, the Commission's Health Care Subcommittee has appropriated the language of "choice" in its recommendations for addressing female inmates' health needs. Specifically, it has recommended offering free "elective sterilization, either post-partum or coinciding with cesarean section" to female prisoners in labor. In order to get around the "elective" problem (since the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation won't cover elective surgeries), the Commission's recommendation is to reclassify sterilization of female prisoners as "medically necessary" in the Inmate Medical Services Policies and Procedures.

Just like relocating women to new "mini-prisons" doesn't address the fact that 4,500 women are currently being incarcerated unnecessarily, offering sterilization to a woman in labor who has just endured a pregnancy in prison, and who knows that as soon as she gives birth, the state will take her child away from her, is not giving that woman a "choice." As Justice NOW points out in its response to the Commission's recommendations:

When people in prison so desperately need yet are denied access to any other elective, "non-necessary" medical treatment such as preventative dental care, reconstructive plastic surgery following gross injury, and special diets for people with serious medical conditions such as diabetes, while affirmatively offering sterilization to a woman in labor can be suggested "medically necessary," the motive is clear.

For more information, visit Justice NOW.

Further resources on women, prisons, and reproductive justice:

- The Birth Attendants (providing doula services to incarcerated women in Washington State)

- Lockdown on Life: Stories from Women Behind Bars (National Radio Project)

Tuesday, February 6, 2007

Correcting justice

Repost of Sacbee, January 21, 2007,

http://www.sacbee.com/325/v-print/story/110693.html

Doing time for every crime has led to California's overcrowded prisons. Now, many people believe it's time to try a different approach.

By Roger K. Warren -

Published 12:00 am PST Sunday, January 21, 2007

There is no responsibility that judges take more seriously than sentencing criminal offenders. The principal purpose of government and the rule of law is to ensure public safety and security. It is to judges that the authority and responsibility to sentence those whose crimes undermine public safety is entrusted. Serious crimes result in unspeakable injury and loss to the victims most directly affected, and threaten the entire community. The stakes for the offender and for the offender's family are equally high. Judges are never more mindful of how grave a responsibility it is to act as a single judge on behalf of an entire community than when carrying out their sentencing responsibilities.

Criminal cases dominate the workload of California judges, who sentence more than 135,000 felony offenders a year. The hardest cases are not those of the most violent or dangerous criminals, or the sexual predators. Those offenders belong in prison and constitute only about 10 percent of the cases. Cases where the law mandates a prison sentence under circumstances that a judge considers unjust are hard, but they are also rare. For many judges the most difficult and frustrating aspect of handling felony cases is dealing with the crushing volume of repeat offenders, most charged with nonviolent crimes, who constitute the vast majority of felony cases. Year after year, California judges sentence repeat offenders to jail and probation, and finally prison, with little hope for success in changing an offenders' future criminal behavior. Over time, many judges grow increasingly cynical and discouraged. Every day, judges see that our current sentencing policies aren't working and question whether there isn't a better way.

California's sentencing policies aren't working because, more than any other state, California relies overwhelmingly on incarceration as the answer to every crime rather than invest in meaningful adult probation services and effective community corrections programs to reduce crime. We need to put the concept of "corrections" back into the corrections profession.

California has the highest recidivism rates in the country and, as a result, the most overcrowded prisons. About half of those sentenced to prison every year are nonviolent offenders previously sentenced to prison but never for a violent crime.

Although criminal records of California prisoners reflect no greater violence than inmates in other states, their records are longer and California inmates are more likely to have been on parole when they committed a new offense. Two thirds of parolees are returned to prison within three years -- twice the national average. Eighty-eight percent of those parolees are returned because of new criminal activity.

As California criminologist Joan Petersilia observed, "California epitomizes revolving-door justice in the United States."

In California, basic sentencing reform is long overdue. In recommending a plan for prison reform, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger noted that thousands of low-level offenders in California today are serving prison sentences with little opportunity for rehabilitation and that implementation of an effective strategy to reduce prison overcrowding and offender recidivism will require a partnership between state and local corrections agencies. His most recent proposal to address the state's prison overcrowding crisis calls for bipartisan cooperation to achieve essential sentencing reforms and reduce California's high recidivism rates. He has outlined a promising, but still incomplete, vision of the path to true prison reform and improved public safety for the citizens of California.

The governor's principal sentencing reform proposal is to create a California sentencing commission. California is indeed out of step with state-of-the-art sentencing structures across the country in failing to have a bipartisan, professional and independent sentencing commission. In 20 other states sentencing commissions are responsible for reviewing proposed sentencing legislation, making population and financial projections, conducting research, coordinating the collection and dissemination of relevant data and making recommendations to policy-making bodies. Sentencing commissions ensure that policy makers have accurate and credible data needed to make well-informed decisions.

Commendably, the governor's proposal budgets $50 million this year and $100 million in following years to improve adult probation services for youthful offenders. But the governor's proposals to reduce recidivism still focus on prison inmates and parolees, and do very little to promote the development and funding of local corrections programs to reduce recidivism among more of the 35,000 offenders sentenced to prison every year for nonviolent offenses. In the long run, the most cost-effective way to slow prison growth and improve public safety is to develop effective community corrections and treatment programs that reduce recidivism -- especially among nonviolent offenders -- before offenders are imprisoned.

Unlike many other states, California provides almost no support for the provision of rehabilitation services to offenders in communities where they and their families live. It is one of only two states where adult probation services are primarily a local responsibility. As a result, adult probation services are drastically underfunded; more than half of the 300,000 adult offenders on probation are not actively supervised. The state has yet to act upon the recommendation made by the bipartisan Little Hoover Commission more than 15 years ago to implement community corrections programs. The California State Sheriffs' Association and California State Association of Counties also have called for implementation of such programs.

Thirty years ago, when California's current sentencing policies were written, there was a great deal of skepticism about whether rehabilitation really works. But today there is a voluminous body of rigorous research that has proven that well-implemented treatment programs targeting appropriate offenders do work and reduce offender recidivism by 10 to 20 percent. The same research also proves that without treatment incarceration does not work to reduce recidivism (beyond the period of incarceration) and in fact increases the likelihood of recidivism.

Unlike California, many other states, including Arizona, Oregon and Washington, are already committed to these evidence-based practices to reduce recidivism. Arizona courts use offender risk assessment tools in sentencing. Oregon courts require sentencing judges to consider the likely impact of potential sentences on reducing offenders' future criminal conduct. The Oregon Legislature has required the state's criminal justice agencies to collect and share sentencing data to determine the effect of various sentences on offenders' future criminal conduct. The state's Legislature also required that 50 percent of funding provided for corrections programs in 2007 be spent on evidence-based programs and 75 percent of the funding in 2009.

Facing the need to construct new prisons, the Washington Legislature called for a study of the existence of any evidence-based corrections alternatives. The study identified a number of evidence-based programs that reduce recidivism by up to 20 percent and found that implementation of the evidence-based options would reduce Washington's crime rates, avoid future prison construction and save taxpayers $2 billion.

Evidence-based community corrections programs promote public safety by reducing recidivism by known offenders and by freeing prison bed space for long-term imprisonment of more dangerous and serious offenders. They allow offenders to be in the work force and pay restitution to the victims of their crimes. They are not soft on crime. They target offenders who present a high risk of reoffense but not violent, dangerous or the most serious criminals for whom long-term incarceration is clearly more appropriate. In addition to providing services to reduce recidivism, the programs can control the risk of offender misbehavior through, for example, local incarceration, intensive supervision, electronic monitoring, day or evening reporting responsibility, testing and surveillance.

For many of these offenders a community treatment program with behavioral controls is a tougher and more effective sentence than imprisonment. For many offenders the responsibility to change their own anti-social behaviors is a lot tougher than doing time. Most nonviolent offenders don't serve long prison sentences anyway. Nonviolent offenders in California serve a median of less than 10 months in prison before being paroled.

Sentencing reforms now enjoy broad public support. Although public safety is a top public concern, the public believes in rehabilitation and doesn't see punishment and rehabilitation as either/or propositions. When asked in a recent nationwide survey by the National Center for State Courts whether they think that once offenders turn to crime, very little can be done to turn them into productive, law-abiding citizens or that under the right conditions many offenders can turn their lives around, almost 80 percent of 1,502 people surveyed say that people can turn their lives around. Eighty-eight percent believe that rehabilitation and treatment programs should often or sometimes be used as alternatives to prison. Seventy-seven percent say they would prefer to see their tax dollars spent on programs to help offenders find jobs or get treatment rather than on building more prisons. The public favors a balanced approach to public safety: an approach that is tough, especially on the most violent, dangerous or threatening offenders, but that also encourages less serious offenders to turn their lives around.

The Little Hoover Commission, which over the past 15 years has published a number of reports on California's correctional system, is planning this week to release its latest report on opportunities for sentencing reform. The commission's report may further guide California along the path that the governor has outlined and may provide a more complete vision of prison reform and improved public safety for the citizens of California.

Guantanamo - black hole or vital tool?

BBC News, January 8, 2007

| By Paul Reynolds World Affairs correspondent, BBC News website |

Five years after the first prisoners arrived at Guantanamo Bay, the detention camp is set for a new phase in the coming months with the start of military tribunals held under a law passed by the US Congress last September.

However, only some 75 of the 395 prisoners there at the moment are likely to face these tribunals, at least in the initial stages. For the rest, there is the prospect of indefinite detention without trial.

The camp - often simply called "Gitmo" and symbolised by the orange jumpsuits worn by prisoners in the earlier stages - remains intensely controversial.

It is seen by the Bush administration as a vital tool in the "war on terror". It is one that enables suspects who are not US citizens to be interrogated and held, indefinitely if necessary, in a US-controlled territory but not subject to normal US court rules.

Critics say it is a legal black hole in which suspects have been abused and face either military tribunals or open-ended imprisonment.

The Military Commissions Act

It has been, and probably will be again, the subject of great legal arguments between the American presidency and judiciary. The US Supreme Court has made two key rulings that have brought the camp more under the supervision of the US congress and courts.

The result of these arguments and interventions is the Military Commissions Act 2006.

This satisfies the administration by approving tribunals where evidence can be brought, and detention without trial where it cannot. Military officers will conduct these tribunals.

The law forbids "cruel" or inhumane treatment, but allows for coercive interrogation, which is regarded as important in gaining intelligence. It also narrows the application of the Geneva Conventions.

It does not satisfy opponents who argue that

- prisoners cannot invoke the ancient right of habeas corpus to challenge their detention in court

- they do not have the full protection of the Geneva Conventions

- the rules for the tribunals are unfair

- harsh treatment is allowed

- for many, there will be no tribunal but only detention

Even close allies of the United States including Britain have called for the camp to be closed. President Bush himself said he would like to see the end of it.

But it remains in being and there is no end in sight.

Tribunals to start

The next move is for the tribunals or commissions to begin, probably in March or April.

Among those to be put in front of tribunals is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, described by Mr Bush as "the man believed to be the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks".

The president also praised the Commissions Act for allowing the CIA to carry out so-called special interrogations, which are believed to include the practice of waterboarding, in which water is poured onto a prisoners face, inducing a feeling of drowning and panic.

"This programme has been one of the most successful intelligence efforts in American history ... with this bill, America reaffirms our determination to win the War on Terror," Mr Bush said.

Amnesty International said on this fifth anniversary: "Guantanamo Bay is a symbol of injustice and abuse. It must be closed down."

And Human Rights Watch executive director Kenneth Roth said: "Detaining hundreds of men without charge at Guantanamo has been a legal and political debacle of historic proportions. It's time to close Guantanamo. The Bush administration should either charge or release the detainees trapped in a nightmarish limbo."

Numbers

In all some 775 prisoners have been at the camp since 11 January 2002. Just under half, 379, have been released.

Fourteen detainees are high-profile prisoners, who had been held at secret CIA prisons elsewhere and who were sent to Guantanamo Bay last September.

It is thought that the tribunals will start with some of them, led perhaps by Khaled Sheikh Mohammed.

But what of those, probably the majority, who will not face a tribunal?

They are subject to an annual Administrative Review Board (ARB) "to determine whether you still pose a threat to the United States or its allies", as a document given to the prisoners states.

The transcripts of the ARB hearings are published by the US Defense Department.

The case of Sami al-Hajj

There are allegations against the suspects but the evidence is in outline only and some of it is given to the board in secret. The source cannot be confronted.

A look at the case of Sami al-Hajj (case 345), illustrates the "limbo" in which these cases can lie.

Sami al-Hajj was a cameraman for the Arabic station Al-Jazeera when he was arrested by the Pakistan police while trying to enter Afghanistan in December 2001.

He has said he was beaten up while being accused of being an al-Qaeda operative. He was later transferred to Guantanamo Bay. His 2006 ARB lasted for 40 minutes.

A summarised version of the case against him was read out before the board went into secret session to hear other claims against him.

The case was that he had been a courier for an Islamic charity called al-Haramayn which the US government has designated as one that "has provided support for terrorist organisations." He is also accused of working with or for individuals who were al-Qaeda figures.

Sami al-Hajj told the board that he had "never been a member of a terrorist group" and that a mistake had been made. He condemned the "tragic attack on the World Trade Center in New York."

His lawyer Clive Stafford Smith says that he did take money to Azerbaijan for al-Haramayn but that it was for charitable purposes. His wife is Azeri.

"I do not think Sami will face a tribunal," said Stafford Smith. "They have really shown little interest in him and this is an obvious and shocking attempt to tread on the media. I think they will release him."

As for the wider issue of Guantanamo Bay, he says that a challenge to the Military Commissions Act is already before the US courts.

"I expect that it will reach the Supreme Court in about a year," he said.

Paul.Reynolds-INTERNET@bbc.co.ukJust say 'failure

Printer on 1-18-07

The War on Drugs hasn’t cut use, but it has squandered billions of dollars and kept our prisons full. That’s why local governments like Sacramento’s are coming to the fore in some areas of drug-policy reform.

By Sasha Abramsky

Photo Illustration by David Jayne |

The second-floor offices of Sacramento’s Harm Reduction Services are marked by two bullet holes. Both from small-caliber weapons, the first took out a small ring of plastic from the accordion connecting the air-conditioning unit to the wall. The second went through the glass of a nearby window.

Located in the heart of Oak Park, on the corner of 12th Avenue and 40th Street in a somewhat rickety old wooden building that used to serve as the surgery center for a local doctor, Harm Reduction Services is, says 55-year-old executive director Peter Simpson somewhat matter-of-factly, on one of the most violent blocks in the city’s most violent zip code: 95817. In this part of the city, like in so many other impoverished communities nationwide, serious drug use, and the violence that accompanies the underground sale of narcotics, is epidemic. It remains epidemic despite decades of War-on-Drug policies and vast amounts of money spent in an attempt to curb the nation’s appetite for illicit substances.

The philosophy of harm reduction essentially takes it as a given that users are a part of life today. From there, it looks to work on solutions that reduce the impact of everyday drug use; in the ultimate analysis, harm reduction serves to limit the body count and reduce the fiscal cost to the taxpayer.

Simpson’s organization works with local users to try to mitigate the health consequences of their actions, providing AIDS testing, giving out educational materials and so on. Other harm-reduction advocates support maintaining heroin addicts with methadone or the newly developed buprenorphine. And some proponents now urge the distribution of Narcan and Naloxon, two drugs developed to counter the effects of heroin overdoses, to addicts, so they can intervene and save lives when users ingest impure drugs or simply put too much into their system.

Taking the theory a few steps further, some analysts also have begun looking at how best to neutralize violent gangs’ control over drug markets and distribution, perhaps through wholesale decriminalization and the creation of legal, regulated and taxable drug markets.

Still, others have begun seeking ways for states to restore access to welfare for drug felons--access cut off in the 1990s as federal politicians looked to shore up their tough-on-crime credentials--as a way to limit homelessness and minimize the spiral back into criminal activity.

The problem is all of this is intensely politically charged. In other words, while it may be good policy, it’s seen to be extremely poor politics. Not to mince words, people are scared to talk about these big-picture changes: County Supervisor Roger Dickinson waited a month to return calls for this article and then failed to follow through with scheduling a time to be interviewed. Former Assemblywoman Jackie Goldberg’s and Assemblyman Mark Leno’s offices didn’t make time for interviews, even though both politicians are known to favor reform of key drug-war policies. After a month of procrastination, spokespeople for the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs decided not to comment.

During the election campaign, neither gubernatorial candidate acknowledged that a change in the state’s approach to drugs might be necessary to curb runaway prison growth--although, in the aftermath of the election, talk has accelerated about the creation of a sentencing commission to look at some of the prison terms handed down to criminal offenders. And it was likely because of the political risks involved in proposing radical reforms around the sanctions attached to drug usage that, in the run-up to the election, Governor Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill that would have restored Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits to ex-drug felons.

“The issue is we need to get people off of intravenous drugs, period,” says Sacramento Police Sgt. Jerry Camous, president of the city’s Police Officers Association. “That’s the hard part. Do whatever it takes to get them off, and quite frankly that’s often through punishment. You still have the underlying problem that people are chasing that high. Incarceration may be a key motivator, or the avoidance of incarceration may be a key motivator [for addicts] to seek that help. Addictive behavior has got to change.”

Toward harm reduction

Nevertheless, despite law enforcement’s reluctance to move away from punishment-based anti-drug strategies, the arguments moving municipal authorities, if not state and federal agencies, toward at least a partial harm-reduction approach are increasingly compelling. A decade ago, the city’s health department estimated that as many as 15,000 people a day in the greater Sacramento area were intravenous drug users. Since then, no large-scale studies have been conducted, so any newer numbers are largely guess work.

But Simpson, himself a one-time substance abuser--his drugs of choice were alcohol and meth--believes that if these numbers ever were updated, researchers would find even more users, of an ever-greater variety of substances, today than in 1996. In an era plagued by AIDS and rampant hepatitis-C infection rates, that raises a whole bunch of uncomfortable health-related questions for the region.

At least in part because of guestimates such as Simpson’s, in recent months the City Council has moved toward legalizing needle-exchange programs within city limits, formalizing a process that has gone on in the shadows for several years and, along with San Francisco, Berkeley, and San Luis Obispo, bringing the city to the fore of drug-policy reform in the state. Assuming it passes--and there is broad agreement that it will--within a few months groups such as Simpson’s will be permitted to set up exchange systems through which addicts may trade in dirty needles for an equivalent number of clean ones.

Complementing this, the council also has voted to opt into a statewide law, SB 1159--signed by Governor Schwarzenegger after being vetoed by governors Wilson and Davis--giving cities the right to allow pharmacies within their boundaries to sell needles over-the-counter.

“We’re trying to control some of the illnesses that come from [drug usage],” explains Councilwoman Sandy Sheedy, one of the most outspoken proponents of the changes. “I don’t know if you’re going to ever clean up drugs, but you can make it safer for the communities around the people using the drugs and their families.”

Absent needle-exchange programs, Sheedy fears increased levels of HIV/AIDS, higher rates of hepatitis-C and a greater prevalence of other blood-borne diseases. “With needle-exchange programs, at least we’re trying. The people who live in the communities where drugs are prevalent are the ones saying, ‘We have to do something about this.’ Needle exchange is part of a continuum. To take the needle and exchange it, at that point you’re able to talk. You’re able to communicate and to educate.”

Yet, while Sacramento’s police department kept silent during the policy debates around these changes--largely sitting on its reservations about the effectiveness of the program when it comes to getting dirty needles off the streets and thus essentially signaling tacit consent for the principles behind the reforms--according to Sheedy and others, the county sheriff’s department is still strongly opposed to such programs. (A spokesperson for the Sheriff’s Department declined to comment on the specific debate around needle exchange.)

And therein lies the rub: Lacking federal reform of Drug War policies that have failed to end America’s drug problem, many states have begun going out alone in pursuit of change. Yet, too many politicians at a state level fear appearing soft on crime, and so all-too-often they pass weak legislation allowing cities to create their own systems around, say, needle exchange, while not imposing uniformity statewide. As a result, a user in Sacramento soon might be able to buy or exchange needles within the city limits quite legally; yet, if they then drive back to their home outside the city limits, they could be arrested by sheriffs’ deputies on paraphernalia charges.

Peter Simpson, executive director of Oak Park’s Harm Reduction Services, knows firsthand that serious drug use--and the violence that accompanies underground sale of narcotics--remains epidemic despite decades of War on Drug policies. Photo By Larry Dalton |

Moralistic, classist enforcement

For more than 30 years, state and federal governments have vied with each other to create an ever-more enforcement-oriented War on Drugs. From New York’s Governor Nelson Rockefeller pushing for lifetime mandatory sentences for certain categories of drug dealers in the early 1970s to federal-sentencing laws and the increasing amounts of money channeled into the prosecution and incarceration of drug offenders, strategies have essentially been based around the “Just Say No” rhetoric, combined with extreme punishment measures when people instead said “Yes.”

Instead of viewing drugs as a public-health issue, first and foremost they have been viewed as a moral scourge, their usage not just socially undesirable but sinful. And, from within this framing device, responses have been crafted accordingly.

“It’s not logic. It’s morals,” Harm Reduction Services’ Simpson argues. “It’s moralistic. ‘I’m going to tell other people what not to do.’ It’s the difference between morals and ethics. Ethics are internal and self-driven. It combines so many high-ticket emotional elements: ‘Protect our kids. The drug users are evil people piece of it. They’re robbing us and endangering us and are scary people.’ Then you have the moral issue: ‘It’s not OK to use drugs.’ And the classist bullshit that goes with it.

“It’s this mishmash of all these different, non-rational bullshits that people roll up together into this Nancy Reagan ‘Just Say No’ message,” Simpson continues. “It doesn’t work. It’s doomed to failure.”

In a sense, the country has spent a huge amount of time, energy and financial resources re-creating the worst collateral consequences that Prohibition generated in the 1920s and early 1930s: increasingly powerful, and vicious, criminal cartels; the siphoning of money into ineffective law enforcement; the creating of conditions in which political and law-enforcement-agency corruption would almost inevitably flourish; the nurturing of a public-health menace fueled by the street sales of impure or poisonous produce that has been manufactured with no regulatory oversight, hit the streets.

Arguably, however, the collateral effects of the War on Drugs are even worse than those accompanying Prohibition. At least in the 1920s, alcohol users weren’t, wholesale, arrested, given felony records and, often at immense cost, then incarcerated for years at a stretch. At least in the 1920s the country didn’t end up with millions of men and women behind bars and hundreds of thousands of children with parents incarcerated for nonviolent, arguably victimless crimes.

Look for explanations for the nation’s booming prison population, and drug policy always figures full-center. As the War on Drugs has developed, more Americans have been arrested for drug crimes, more are prosecuted, more are sentenced to prison and the prison terms themselves have become longer. At the back end, as more and more addicts return to their communities, they are prevented from accessing many jobs and most forms of welfare. All too often they are busted back into the criminal-justice system after submitting dirty urine to parole officers or drug-treatment providers.

“It’s a whole societal issue that people tend to put off on law enforcement,” says Sgt. Tim Curran, spokesman for the Sacramento County sheriff. “But we can’t solve or cure it on our own. Law enforcement is not going to solve the problem. It’s a Band-Aid. So we do need social programs that help prevent the problem.”

California’s prison system now holds more than 170,000 inmates. The state spends about $9 billion per year maintaining its correctional apparatus. Its prisons are filled to nearly twice their intended capacity. The governor recently declared a system-wide emergency and began shipping inmates out to private prisons in other states. And, in the coming months, there is a considerable likelihood that the courts are going to impose a population cap on the system because of the dangers of overcrowding.

Why? Well, in large part because, despite falling crime rates over much of the past 12 years, more and more people are being incarcerated because of drugs or drug-related crimes. Of the 65,000 people booked in Sacramento County’s main jail each year, Curran estimates that about 85 percent of them are drunk, high or otherwise under the influence when they are arrested.

Lacking a voice, drug users make an extremely easy political target. In the 1990s and early 2000s, governors Wilson and Davis both staunchly opposed relaxing the state’s no-nonsense penalties for drug-related crimes. More recently, former state Senator Charles Poochigian, defeated in his bid to become attorney general, even went so far as to propose further jacking-up the prison terms for drug criminals.

Nationally, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, using numbers generated by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, estimates that by the early years of the 21st century, more than 450,000 people were behind bars on drug charges. The Bureau itself reports that while 38,541 people were sent to prison for drug crimes in 1986, by 1996 that number had increased to 148,092. And the trajectory on this continues to be upward-pointing. By 2003, 37 percent of all charges filed in federal court were drug-related.

“The drug wars have been a giant crime-creation program,” argues Dale Gieringer, California coordinator of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. “Twenty-two percent of all arrests in California are for drug offenses that didn’t even exist in my grandparents’ generation.” (Up until the early 20th century, Gieringer explains, the sale of drugs in the United States was almost entirely unregulated, and hence many users were able to live relatively normal lives without repeatedly bouncing into the criminal justice system.)

By any rational measure, the War on Drugs has been one of America’s greatest domestic policy failures. It has singularly failed to stop the usage of traditional narcotics such as heroin and cocaine, in the same way as Prohibition utterly failed to curb alcohol consumption; to prevent the emergence of new epidemics around methamphetamine, OxyContin, ecstasy and other designer drugs; and to significantly reduce the numbers of young people willing to serve as drug mules and street dealers.

Meanwhile, its body count and cost--financially, with the country now spending tens of billions of dollars a year on coercive anti-drug efforts, and morally--puts it on a par with a failed, and increasingly bloody, military intervention overseas such as that currently playing out in Iraq.

“Despite the major efforts of the drug wars--the $80 billion a year--drug use has continued unabated,” says epidemiologist Rachel Anderson, executive director of the Sacramento-based Safer Alternatives thru Networking & Education. “Everyone knows someone who uses drugs.”

Decriminalization creates strange bedfellows

Recognizing this, in recent years an increasing number of commentators, public-health experts and even politicians have been willing to step outside the box on this issue and critique the underpinnings of the War on Drugs. Many critics are political progressives, children of the 1960s who themselves dabbled with drugs, or African-American spokespeople concerned about the racial impact the war has had. But a surprisingly large number of these individuals are from the right of the political spectrum: The critics now range from NORML all the way to the Committee To Regulate and Control Marijuana, a Republican-dominated group that sponsored the marijuana-legalization initiative in Nevada that got 44 percent of the vote in November.

Sacramento City Councilwoman Sandy Sheedy is an outspoken proponent of needle exchange. "I don’t know if you’re going to ever clean up drugs, but you can make it safer for the communities around the people using the drugs." Photo By Larry Dalton |

The late monetarist economist Milton Friedman was on record supporting drug decriminalization. Ex-Secretary of State George Shultz favors a similar approach, as does one-time New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson, who concluded that wholesale decriminalization would remove a huge pool of money from organized crime and would significantly boost tax revenues for the state, allowing it to reinvest the money in tested anti-addiction and public-health programs. In California, Tom McClintock, a fiscal conservative with libertarian leanings, has shown some sympathy to these arguments, earning distinction as one of the only Republican legislators to vote in favor of medical marijuana.

Yet, the innovation policy-wise is not coming from the federal level, which remains stubbornly wedded to traditional search, seizure, prosecution and incarceration strategies, but rather from states and cities. States like New York, Michigan, Louisiana and Connecticut all have significantly modified their mandatory-sentencing laws. And electorates in cities such as Denver have urged their municipal authorities to stand down when it comes to enforcing anti-marijuana codes.

Where does California, the most heavily populated state in the union and historically one of the most schizophrenic when it comes to drug policy, fit into all of this? After all, some of the most liberal, but also some of the most conservative, drug- and criminal-justice policies originate here. In fact, despite much-touted reforms in recent years, such as the passage of Proposition 36, by many measures the state is one of the harshest in the country when it comes to the enforcing of anti-drug laws.

By 1999, 132 per hundred-thousand of the state’s residents were in prison on drug convictions, and over a quarter of a million Californians were being arrested annually on drug charges. According to an analysis of state numbers by the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, before the treatment-oriented provisions of Proposition 36 kicked in more than half of the state’s drug prisoners were serving sentences for possession.

“In California,” says psychiatrist Dr. Peter Banys, one-time president of the California Society of Addiction Medicine and currently in charge of the San Francisco-based Methadone Access program, “there is a debate, not a particularly light-producing debate, but it produces a lot of smoke. It’s a debate between the incarceration industry and the treatment industry. The treaters don’t want to be seen as legalizers, and the criminal justice people, this is feeding their pipeline. When the majority of people arrested in the state are for drugs, you’ve got to keep your crops growing. It’s about crops and crop rotation. We now arrest more people for possession than for drug sales or manufacture.”

In other words, everybody who wants to be taken seriously prefaces their arguments by saying “of course drugs are bad and should remain illegal. ... And here’s how we think our solution works better ...” Few are willing to say something to the effect of, “The current system’s underpinnings no longer make sense. Why not let the market sort this one out? If drugs are bad, most people won’t take them--and those who do, well, they’ll take them whether they’re legal or not, so why not take the punishment component out of anti-drug policy and move toward a more aggressively treatment-based system?”

California has one of the most progressive medical-marijuana laws in the country, putting it at odds with the federal government and making it “head and shoulders above everyone else” on the issue, according to Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the New York-based Drug Policy Alliance. But at the same time, it has a three-strikes law on the books that has put many prisoners away for life on third-strike drug-possession crimes that, in and of themselves, hardly merit attention.

Similarly, voters enacted Proposition 36, which channeled tens of thousands of drug criminals into treatment rather than prison. Yet at the same time sheriffs in conservative counties still arrest two-bit users on paraphernalia charges and district attorneys, supported by police associations, have launched a concerted effort to undermine Proposition 36.

“Prop. 36 basically made a mockery out of the criminal-justice system,” Sgt. Camous asserts. “People are arrested for various levels of controlled-substance possession and the DA’s office reduces [the charges] because of Prop. 36 and puts them into diversion. I don’t have the statistics, but I’d say most of the diversion efforts fail.”

In the same schizoid vein, the state has deprioritized pot possession, making it a ticketable misdemeanor offense. State Senator Gloria Romero’s SB 797, supported by other elected legislators like Goldberg and Leno, who have spoken out in favor of redefining drug policy as a public-health rather than criminal-justice issue, would have lowered it still further, to an infraction.

Still, young gangbangers can be arrested and processed into the system for smoking pot in public, the arrest giving law enforcement probable cause, or at least pretext, to search homes, persons and cars in pursuit of evidence of more serious crimes. (In other words, pot is a gateway drug, not, in this context, to harder drugs, but to law enforcement looking for evidence of more serious criminal activity.)

As a result, despite all the reforms in this arena, the Drug Policy Alliance estimates there are 60,000 marijuana arrests per year in the state, one-third of which involve African Americans. NORML has calculated that about 1,400 people in the state are actually serving prison terms on pot convictions, up from a mere 100 in 1980.

Cities and counties are allowed to opt into a law allowing pharmacies to sell needles over the counter, and they also are allowed to create their own mini needle-exchange programs. But there is no statewide policy on this, leading to a jurisdictional chaos. Similarly, individual schools can choose to use alternative anti-drug education systems to that of DARE. Some high schools in Oakland, for example, recently have brought in a non-coercive, peer-education-based program called UpFront. Yet, the default assumption remains that most drug education, like religious-based sex education, will be abstinence-based, firmly on the DARE model.

A more rational drug policy

For the harm-reduction advocates in town, their presence looming large in public-health circles but failing to impact significant numbers of legislators, the slowness of change is infinitely frustrating.

How would Simpson devise a more rational drug policy for the city and state? “I would acknowledge that most people who use drugs are going to keep doing it. Even if there was treatment on demand, most of those who are daily drug users today are still going to be users tomorrow because sobriety happens rarely. So, all of the policies have to be based on the fact we have a drug-using population that’s going to continue to use.”

Instead of mandating people behave in a certain way, Simpson believes a more effective strategy would be to ask the following question: “How can your life be more functional?”

Perhaps, ultimately, that’s the most sensible question that any drug-policy crafter can ask. Less utopian than the dream of absolute prohibition, but pragmatically more effective, the question leads to a host of policies and programs that, in a rational world, would shape policy in this arena over the coming decades.

That’s where Sacramento seems to be heading with needle exchange. It is where, ultimately, legislators in the Capitol ought to head as they continue to debate statewide reforms and continue to ponder how to deal with the problems plaguing the state’s oversized, underperforming prison system.

“I don’t know if we win the war on drugs,” Councilwoman Sheedy says, sitting in her fifth-floor office in City Hall. “But we must find a way to make sure public health is taken care of.”